At first glance, the six police records on Andrew Jordan’s computer screen appear nondescript. Each one includes a timestamp, evidence ID and event numbers, and basic demographic information about a police officer. This is the metadata a Chicago Police Department body-worn camera generates every time an officer turns it on.

It’s a far cry from the police body camera footage that has lodged itself in the public’s consciousness in recent years, sparking protests and calls for reform throughout the United States. By comparison, these datapoints don’t seem like much.

But Jordan and his Washington University colleagues have acquired 15.7 million of these metadata records, allowing them to tackle pressing questions about policing with big data. They’ve begun cross-referencing them against Chicago Police Department records of arrests, investigatory stops, and uses of force. And now they have a National Science Foundation grant of nearly $225,000 to help them in their efforts.

With the NSF grant and ongoing support from the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures (ITF), a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan, Jordan and his collaborators have an unprecedented opportunity to study a central question surrounding police body-worn cameras: When camera activation is left to the discretion of individual officers, what motivates them to turn the camera on – or leave it off?

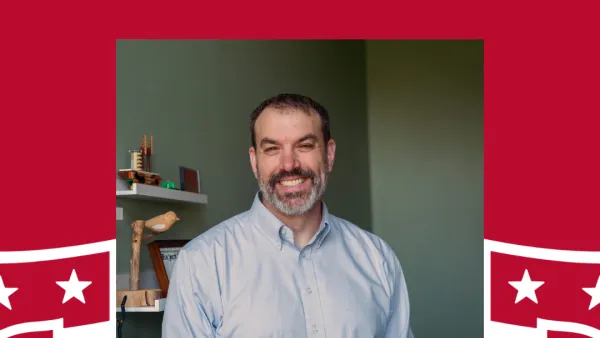

“There are a lot of questions that are simple, yes, but still haven’t been answered,” Jordan said. “No one has put together a clear picture of when cameras are and aren’t activated. There are studies that say activation rates are not 100%, but they don’t have the kind of metadata you would need to really dig into the situations where they are or aren’t activated.”

An assistant professor in the Department of Economics, Jordan’s field of expertise is applying economic principles of incentive-based decision making to the criminal justice system. He joined WashU in 2021 as part of the first cohort of hires under the Digital Transformation Initiative led by Feng Sheng Hu, the Richard G. Engelsmann Dean of Arts & Sciences.

Jordan was on the hunt for new projects when he happened upon an intriguing item on MuckRock, an online database of public records requests. Someone had filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to review the Chicago Police Department’s body-worn camera metadata, specifically covering the weeks of protests after the 2020 death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Jordan dug into the metadata that resulted from that request and immediately saw the possibilities. If he could analyze all of the CPD’s body camera metadata, dating back to when the cameras were first adopted in 2016, he could unlock a treasure trove of information about when, where, and why officers activate or don’t activate their cameras, including situations when leaving them off violates CPD bylaws.

But he couldn’t do it alone. To gather, analyze, and decipher this data, he needed to look at policework from a variety of different perspectives.

“There’s the social stuff, which I’m a little attuned to as an economist, but you want people who can talk confidently about that,” Jordan said. “And then there’s also the complicated statistical stuff of getting the datasets actually lined up properly, which I wanted to make sure I did correctly.”

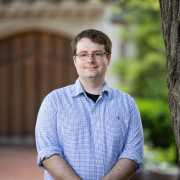

That need for cross-disciplinary expertise led him to the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures (ITF), an initiative that works to connect WashU faculty from different academic backgrounds with the goal of fueling groundbreaking collaborations. Jordan reached out to ITF co-directors William Acree and Betsy Sinclair, who put him in contact with Soumendra Lahiri, the Stanley A. Sawyer Professor in Mathematics and Statistics, and Christopher Lucas, assistant professor of political science.

The Police Body Camera Metadata group of Jordan, Lahiri, and Lucas received an initial seed grant of $89,000 and launched in 2022, along with eight other multiyear ITF clusters.

Since then, the group has filed more than a dozen public records requests with the Chicago Police Department to gather the 15.7 million metadata records, as well as millions of additional records containing information on arrests, stops, 911 calls, complaints filed against officers, and more. These records are spread across dozens of spreadsheets, none of which were compiled with data scientists in mind. Preparing these messy datasets for analysis will be one of the most labor-intensive components of the project, Jordan and Lahiri said.

“At this early stage, we are working with a subset of the data,” Lahiri said. “Even with that smaller dataset, it’s not easy.”

One key to connecting the disparate datasets is a consistent 10-digit event number assigned to each incident. In many cases, these numbers help to link body camera activation records to other incident reports. But event numbers aren’t always present – in the six metadata records Jordan pulls up as examples, two of them are missing an event number. In other instances, an event number that appears in the body camera metadata doesn’t appear in other incident reports.

“That's when things get difficult and what we need our statistical model for,” Jordan said. “It can use information about an arrest – when it happened, where it happened, what officer made it – to say if any of the body-worn camera recordings the officer made that day could match to that arrest. If we find that none can, then we think the officer did not activate their camera.”

Fine-tuning that model to accurately identify non-activations will allow the team to conduct a deep-dive analysis that will potentially reveal patterns in body camera inactivity. Among the questions the team hopes to answer: Are officers less likely to activate their cameras at certain times of day? When responding to certain types of incidents? In certain parts of the city?

“If we know what those characteristics are, that will inform the best practices in those scenarios,” Lahiri said. “Of course, there are two sides to this. We are looking at the data; the police officers have to handle the situation on the ground. And if we isolate these situations and characteristics, they will probably come up with better ways to address those incidents.”

Given the thorny, political nature of police conduct, these early, data-intensive stages of the project are crucial to establishing credible findings. From there, the transdisciplinary nature of the Police Body Camera Metadata team will equip it to interpret the results from a variety of different angles, including economic, statistical, and legal. Jordan estimates the entire project will take about two years to complete.

“With most of these problems, there are many dimensions,” Lahiri said. “Having people look at it from different perspectives, I think, can give you a solution that is closer to the real-life solution you’re seeking, rather than statisticians who primarily focus on the numbers and come up with a model. All of those perspectives must be looked into. It’s going to impact people’s lives.”